The fictional serial killer “Hannibal Lecter” could request a parole hearing under Washington House Bill 1189. He would have to show remorse and that he has changed, which unfortunately psychopaths are very good at faking, in order to be released.

Currently forty-nine U.S. states have a “life without parole,” option for the most heinous offences in society. The only state without one is Alaska, which has a total population less than Pierce County.

Like most states, Washington has treated life without parole as a more-humane alternative to the death penalty in aggravated murder cases, and our state’s residents have largely adjusted to this change even while the capital punishment debate continues. After “Green River Killer” Gary Ridgway, received life without parole for the unthinkable cold-blooded rapes and murders of dozens of girls and young women, no criminal has yet been found to have committed worse crimes, so life without parole became a new standard for Washington’s most heinous. The ACLU was an advocate of this change, making the case that Life Without Parole gives victims closure faster than the Death Penalty because it is set following conviction, and survivors can move on without participating in endless appeals. Per the ACLU in the link above: “For these reasons, the survivors of murder victims often feel that the death penalty system only prolongs their pain and does not provide the resolution they need, while the finality of LWOP (life without parole) sentences allows them to move on, knowing justice is being served.”

Life without parole is considered such a definitive sentence in our state that the usual “risk assessment report” often required for other sentences by RCW 9.94A.500 is waived for life without parole cases, and therefore no risk report is part of the court record.

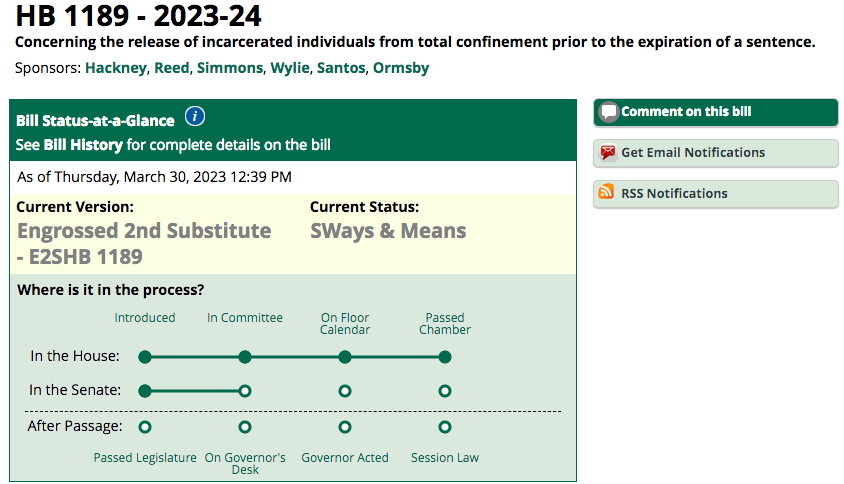

But now the Legislature is embarking on eliminating life without parole in House Bill 1189, and it’s not very well known. It’s rolled into the creation of a new parole system for lesser sentences, which might be appropriate for lower level crimes, but the two issues should each be considered separately for the benefit of the legislature and the public. i.e Legislators should be able to vote on whether to create a parole system, and vote separately on whether those who have been sentenced to life without parole should become eligible for parole. The two issues are entirely different. There is even a third issue, life without parole in the case of three-strikes offenders who did not murder but committed three serious crimes; this group should be discussed in a specific debate.

By discarding life without parole entirely, the legislature makes a mockery of the victim-closure argument that has been promoted by ACLU and others in fighting capital punishment for cold-blooded murderers. Victims who have lost a loved one to a heinous murder would now find it necessary to keep every piece of evidence, every sad photo, and every distressing journal entry for the rest of their lives. They will be at the beck and call of the murderer who destroyed their family and the parole board. Witnesses and investigators will be on the hook also, needing to keep their memories, notes, and photos as sharp as possible, prepared to go talk about the devastating crime every three years (starting at year 20) on the perpetrator’s preferred schedule. As witnesses die, their memories grow fuzzy, or their grief can’t stand another round of testimony, the killer’s demeanor and level of demonstrated remorse will become the primary testimony the parole board has.

It’s even worse as a retroactive bill, since victim’s families may have destroyed tragic momentos and documents covering their most horrible moments of their lives under the promise that the one who took everything from them was locked up for life. The data the parole board needs for a meaningful decision is completely gone in these cases.

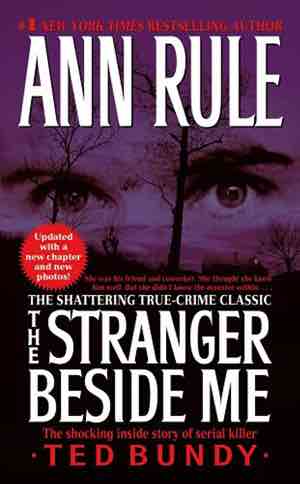

One of America’s greatest true crime writers, Ann Rule, worked for the Seattle Police Department and wrote articles for True Detective magazine in the 1960s and 70s. She volunteered at a Suicide Hotline with a charming young law student named Ted Bundy, who unknown to Ms. Rule was raping and killing young women in Issaquah, Ellensburg, and Seattle. After dozens of murders in our area, Ted Bundy killed again in Utah, where he got caught and arrested. Ann Rule was sure it was a miscarriage of justice, and remained friends with him even as he escaped custody in Utah and drove to Florida, where he killed more women in a sorority. Again not believing Ted Bundy capable of such crimes, Ann Rule attended his trial every day, and sat near him to show support. In her book “the Stranger Beside Me” she summarized her feelings of shock, then sickness, disillusionment, and confusion when toward the end of the long trial, after seeing witness after witness, it began dawning on her that her friend Ted might be guilty. Her story was later used to help FBI in their training, and her book should be required reading for anyone who thinks that a parole board could sit in a two-hour parole hearing with a psychopath, and determine whether the psychopath is safe to go back in society.

A parole system of lessor crimes may still be of value. As I mentioned above, currently anyone sentenced for any crime after July 1, 1984, is not eligible for parole in Washington. For people within a year of finishing a prison sentence, parole can offer the advantage that Department of Corrections can oversee their reintegration into the community. By paroling them out of total confinement 6-12 months early, the department can set conditions that they have an appropriate place to live and work, which will hopefully carry over after their sentence is complete. This bill creates a new parole system, which should be separated from the discussion of how to handle people sentenced to life without parole. This bill also doubles the size of the clemency and parole board from 5-10 members, and then specifies that five of the members will be randomly selected for each review, leaving it up to everyone’s guess how any hearing will likely go. It also changes the term “offender” to “individual” throughout the existing relevant statute.

The HB text can be found here, and it is a somewhat challenging read with fourteen pages comprising multitudes of strike-throughs and new additions.

For those that want the bottom line, if approved the new bill will include these sections:

(a) Any incarcerated individual subject to total confinement for life without the possibility of parole not be considered for release until the incarcerated individual has been judged to no longer be a threat to society and has served at least 20 years in total confinement or 25 years in total confinement if the incarcerated individual was sentenced pursuant to chapter 10.95 RCW;

NEW SECTION. Sec. 7. A new section is added to chapter 9.94A RCW to read as follows:

(1) The board may take any of the following actions: Deny a petition without a hearing because the incarcerated individual does not meet the initial criteria for filing a petition; or conduct a hearing in accordance with RCW 9.94A.885 to consider additional information, and then deny the petition or recommend commutation to the governor.

(2) In making its decision, the board shall consider, if available, the following factors and information:

(a) Public safety;

(b) The incarcerated individual’s criminal history;

(c) The nature and circumstances of the offenses committed, including the current and past offenses;

(d) The incarcerated individual’s social and medical history;

(e) The incarcerated individual’s acceptance of responsibility, remorse, and atonement. If the individual submitted an Alford plea, the impact that may have on an individual’s ability to provide evidence of remorse, atonement, and self-reflection in relation to the offense committed;

(f) Evidence of the incarcerated individual’s rehabilitation, including behavior while incarcerated, job history, education participation in available rehabilitative program and treatment, and serious infraction history;

(g) Input from the victims of the crime;

(h) Input from the police and prosecutors in the jurisdictions where the incarcerated individual’s crimes were committed;

(i) Input from persons in the community pledging their support of the incarcerated individual, if released;

(j) The available resources in the community to help the incarcerated individual transition to life outside of prison;

(k) A risk assessment and psychological evaluation provided by the department;

(l) The sentencing judge’s analysis in imposing an exceptional sentence, if any;

(m) Statements of correctional staff, program supervisors, and volunteer facilitators regarding the incarcerated individual. Such statements shall be voluntary and withheld as confidential. The board shall not publicly identify the names, content, or statement in the hearing or its written decision;

(n) Any other relevant factors.

I am so curious where you got this information from ??? Please let’s have a conversation about the clemency process and how WA has some of the longest sentences and no parole

Thanks for the comment Loren. I appreciate hearing different perspectives, and I learn from them.

The information is all from the legislative record that I provide links to in the article. These are the official Washington State records, on the official government website. The discussion is going on right now in the legislature, and has not been covered well by media. I’ve had other people on facebook point out that this information is different than what they’ve seen in the media, and that is in fact why I post it here. I know from working in government for 28 years that very often the media gets things wrong, so you have to go to the source.

The Ann Rule section of the article comes from Ann Rule’s book, “the Stranger Beside Me,” which I highly recommend because of the extraordinarily unique situation she found herself in. She’s also an outstanding writer.

As I said in the article, I see the advantage of creating a parole system in our state for lower-level offenders who will to be released eventually when their sentences end. Parole is a good way to help them reintegrate into society with Department of Corrections oversight, and achieve a healthy reunion with their families. I see the creation of this parole system as an easy win if it was not tied to reversing all of the “life without parole” sentences,” which are a different debate. While I alluded to it but didn’t say it in my article, one of the biggest problems with reversing all the “life without parole” sentences is it will reinflame the capital punishment debate, as families of victims will again demand closure and the life sentence with parole hearings every three years (after year 20) will shape up to be the opposite of that. I also explain in my article that three-strikes offenders that have not killed but were sentenced to life in prison need their own debate.

I welcome discussion about this, and if you disagree with specific points I’ve made you are probably not the only one. So feel free to post more details of your concerns if you like.