Public Access Provisions remain an element of controversy in Renton’s proposed SMP. This is not surprising, as the issue essentially pits the US Constitution (which states “…nor shall property be taken for public use, without just compensation”), against the Public Trust Doctrine, the ancient premise the public ownership of our waterways transcends lawmaking altogether (e.g. no law can take the oceans and certain other waterways away from the public.)

Throughout our county there have been countless legal battles regarding waterway access, that usually come down to balancing the US Constitution and The Public Trust Doctrine. And every law produced by congress, the state, the county, or a city, is subordinate to these two supreme codes. Since the Constitution and the Public Trust Doctrine are both nearly unchangeable and open to broad interpretation, the judicial branch currently has more power to affect laws regarding water access (through case-law decisions) then any legislative body in existence. And courts have been doing so.

Still, the City of Renton has been tasked by the state with developing broad, constitutionally acceptable public access rules for waterfront property in Renton. The State Administrative Code specifically says “Local governments should plan for an integrated shoreline area public access system that identifies specific public needs and opportunities to provide public access. … The planning process shall also comply with all relevant constitutional and other legal limitations that protect private property rights.” So as part of the SMP process, we are attempting to construct our public access laws knowing full well that we are not the final authority, and that we could end up in court like so many other jurisdictions have if we don’t balance the interests just right. (Wish us luck!)

So how do we do it? I can only speak for myself on this topic. Here are some of my most candid thoughts.

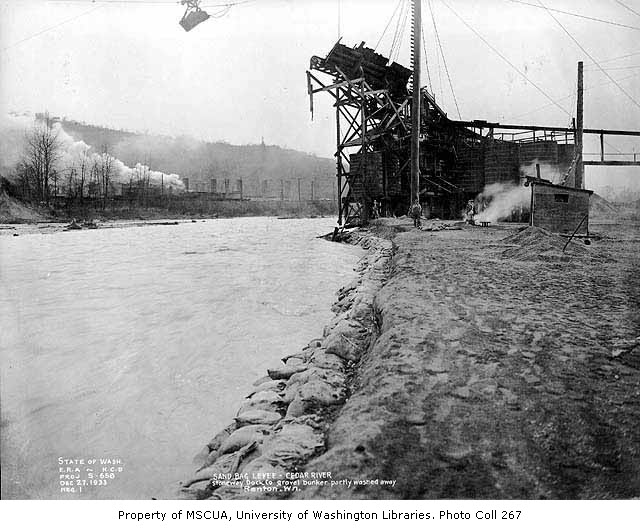

Boaters should feel free to travel on our lake, and float down our river, with no interference or admonishment by property owners. If two kids in a rubber raft need to stop in the mud at the edge of the Cedar River to re-inflate their boat, I believe they have that right under the Public Trust Doctrine, even if the upland property owner would prefer they not stop there. Likewise, if a fisherwoman in hip waders wanders in the shallows next to your riverfront property, you should let them fish– they have a supreme right to be in the river.

Children on the tide lands getting yelled at by territorial homeowners or their agents is too common in our area. I took this picture after witnessing such an altercation last summer at the edge of Salt Water State Beach. New state shoreline rules, and court decisions in other states favoring the Public Trust Doctrine, suggest that public access to Washington’s waterways will be increasing. This is particularly true of our tide lands, which many people feel are part of the ocean– the argument is that the state never owned the ocean, so it therefore had no right to sell part of it.

If our city bordered Puget Sound, I would be aggressive with public access there as well. If a photographer is looking at tide pools at a public access point on Puget Sound, and they spot an unusual star fish 20 feet away in a tide pool in the tide flats below a private residence, I believe they have a right under the Public Trust Doctrine to scramble to the stafish for a closer look. (Be aware there are waterfront property owners who would disagree with me, and some of them are stubborn; so be prepared to get in a confrontation if you try this. Some will argue that their great-great-grandfather purchased the tide-flat from the state years ago. But a growing body of case law says that the state never owned the sand and tide pools between the low and high tides, and hence could not sell this resource to a private homeowner. This issue has not been resolved in our state.)

Bottom line, I’m progressive on water access. Don’t get between me and a tidepool in THE PUBLIC’S tide-flats, and we won’t get into any arguments. And don’t try to stop me from floating past your property on the PUBLIC’S river, and we will be just fine.

However, once you get above the high water mark of the body of water, public access rights become murkier or non-existent. The sandy areas of saltwater beaches are widely in dispute on this point, because of the presence of annual extreme high and low tides which make the limits of the ocean disputable. Courts have had an easier time finding a bright line for property ownership on freshwater lakefront, when the water line is relatively constant. River boundaries are not as easy to define as lakes, but perhaps easier than salt-water beaches. In all these cases, land which is never underwater is generally assumed to be eligible for private ownership.

This is where the constitution comes in. As a councilman, I have been officially sworn to uphold the US Constitution (along with the laws of the state.) And the fifth amendment of the US Constitution makes it clear that private property can not be taken by the public without “just compensation”. What constitutes “just compensation” is clearly open to debate, but it is often a cash payment. It can be something else of value.

Our proposed SMP asks property owners in some cases to dedicate an easement for a trail across the dry portions of their property (above the high water line), and to physically construct the trail as part of their development. In some circumstances this is required outright, and in others it is a condition of being able to develop a larger project closer to the water.

While I love waterfront trails myself, this could raise the question of whether “permission to build” is in itself “just compensation” for the trail dedication. Evidence in favor– developers often dedicate roads and utilities to the city when they build, as part of the development agreement. Evidence against– these roads and utilities are almost always connected to the development project, and are necessary for access and operation of the building; a waterfront trail for the public is somewhat different. Evidence in favor– we require developers to either build park amenities or contribute to a parks fund when they build. Evidence against–a public waterfront trail may be above and beyond the typical burden placed on a developer, and I do not know if we have offered to waive the parks fee as part of the SMP.

In summary, balancing the public access rights with the private property rights is a complicated and often controversial process. We will discuss this topic as part of our final council deliberations on the SMP tomorrow night.

Click here for more complete text from some of the referenced documents

Recent Comments